How are you making ends meet in this economy? We want to hear your story. Email us at CheckbookChronicles@nbcuni.com

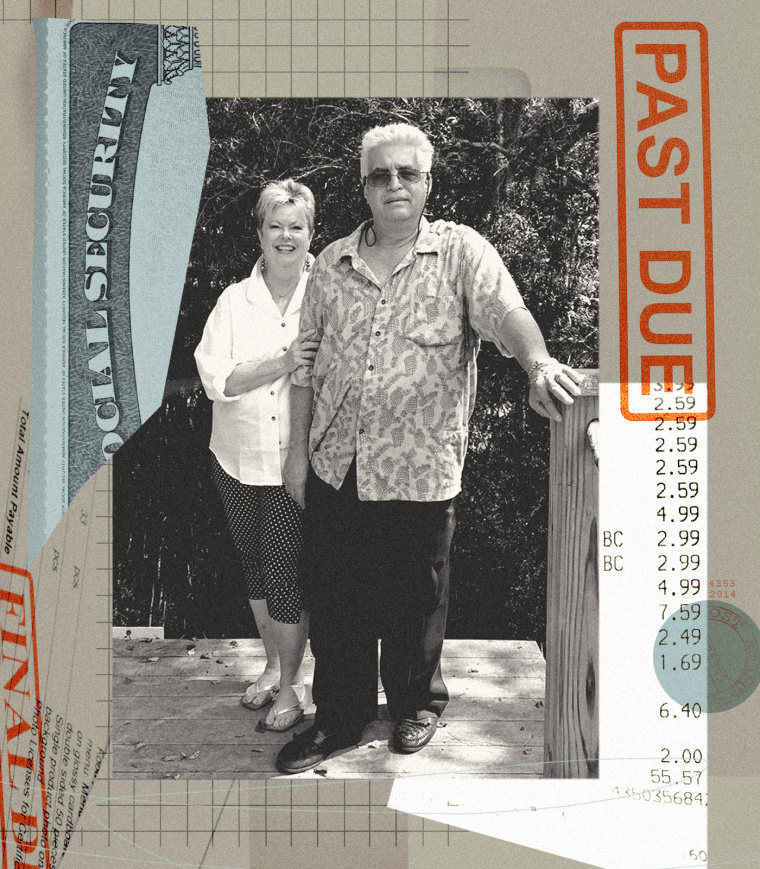

Lucy Haverfield, 71, Florida

- With her retirement savings drained, she's living on $2,400 a month in Social Security.

- Rising food, utility and insurance costs have cut into her already tight budget.

- She frequently skips paying bills to afford food, mostly frozen vegetables and canned goods.

Retirement hasn’t been what Lucy Haverfield envisioned.

“I thought my 60s were going to be my golden years. I would watch commercials, and all I saw were people on trips to Cancún or golfing or sitting by the pool. I couldn’t wait,” said Haverfield, 71, of rural Alva, Florida.

“My 60s were nothing like that — nothing,” she said. “Not even remotely like that.”

Primary source of income: Widowed and with her retirement savings drained, Haverfield lives on $2,400 a month in Social Security benefits, totaling $28,800 a year. She said it isn’t enough to afford fresh fruits and vegetables, let alone a meal at a restaurant or a vacation.

Living situation: Haverfield owns her home in Alva, a small community about 20 miles inland from Fort Myers, with mortgage payments of $1,500 a month. When her homeowners insurance doubled recently to $4,000 a year, she had to borrow money from a friend to cover the cost.

Economic outlook: The broader economy feels rocky, Haverfield said, but she doesn’t think much about it because it’s beyond her control.

“It’s like Alcoholics Anonymous: ‘One day at a time.' I’m going to pay this bill today. I’m not going to worry about the bill after that,” she said. “That’s my economy.”

Before she retired about a decade ago to care for her ailing husband, Haverfield taught at a community college and worked in a variety of senior-level telecommunication roles in South Florida. She and her husband lived comfortably when they were both working — eating out, driving the cars they liked and maintaining a small savings account for trips.

The couple had planned to retire with $1 million in savings between their IRA and their 401(k). But Haverfield said her husband did a poor job managing their finances, especially as he became ill, and she retired several years earlier than planned to tend to him full-time. Their money quickly dwindled to pay for his care, as well as that of her mother and several other ailing relatives.

“We just didn’t anticipate what it would look like for us as caregivers,” she said, describing a financial whiplash many older Americans are confronting as health care costs gobble up their reserves. “We never thought that we wouldn’t make enough money or that the funds wouldn’t be enough.”

Haverfield is among millions of retirees living on fixed incomes outside of a historically strong labor market and rising wages. One in 7 retirees get nearly all their income from Social Security checks, which average around $1,900 a month, according to AARP. Future retirees are set to follow the trend, with 20% of adults over 50 having no retirement savings.

Even so, Haverfield said, “I’m doing OK. I mean, I still have the lights on — some of them don’t work, but the lights that are working are on. I still am able to pay the mortgage. I have a roof over my head. I still enjoy living.”

Budget pain points: Inflation has hammered Haverfield’s basic living costs. She recalled a recent month when the only food she could afford was a loaf of bread, a jug of milk and a bag of onions. The last time she ate at a restaurant was more than a year ago, she said, and her friend paid.

Sometimes Haverfield skips paying one of her bills to cover food and gas, only to pay a late fee the next month, she said. Desperate to trim her electricity costs, she turns off circuit breakers for any appliances she isn’t using and leaves the heat off in the winter, when temperatures can dip into the 50s.

We never thought that we wouldn’t make enough money or that the funds wouldn’t be enough.

Lucy Haverfield, 71, Alva, Fla.

Canned goods like tuna and canned fruit, along with pasta and frozen vegetables, have become staples in her diet. “I would love to have fresh berries in this house — I would love it, it would be amazing — but that’s not to be,” she said.

Florida has suffered some of the highest inflation in the country, driven in part by rising housing, food and insurance costs, according to Moody’s Analytics. Though the state has had one of the lower unemployment rates in the country, wages haven’t been keeping up with rising housing costs, even in more affordable areas, Zillow researchers have found.

Getting by without a cushion: Without any type of emergency fund, Haverfield said, she worries that a major expense, like a car or air conditioning repair, would push her finances to a breaking point. She would have to place any large unexpected purchase on a credit card, but she doesn’t know how she’d be able to make even the minimum payments given how tight her budget is already.

Despite being in her 70s, she has considered trying to get a job but worries about the cost of gas and the wear it would put on her 11-year-old car. Most job opportunities would require at least a 40-mile round-trip drive from her home, she estimates.

So for now, Haverfield is focused on avoiding financial calamity as best she can.

“It’s just: survive,” she said. “That’s it.”