Comedian Gadiel del Orbe always heard his brown-skinned Dominican father say their family came from Spain or the Canary Islands, but their more obvious African roots never came up.

When del Orbe got his DNA test results four years ago, he learned his direct maternal line was related to the Tikar people of Cameroon. He didn’t expect to get emotional, but he started crying once he heard the Tikar are renowned dancers.

“I love dancing. I do comedy, but dancing is my life — bachata, merengue, salsa,” del Orbe said. “To know that the Tikar people are known for dancing just answered questions about me. Things about me align with my ancestors.”

For del Orbe and other Latinos, technological advances and greater access to DNA testing are proving what they long suspected: Their family histories, which were long focused on their white, Spanish ancestry, include African roots and the legacy of slavery.

Family ties to both enslaved and colonial ancestors — including slave owners — can now be uncovered in free online databases, digitized archives and AI-powered indexing, which provide unprecedented access to documents from Latin America and the Caribbean.

Discovering these personal ties is often an emotional process, and many Latinos are using that knowledge to rethink their own identities and their past. They’re also filling the gaps of incomplete family histories that have been passed on for generations.

‘What were they hiding?’

Growing up in the Bronx, genealogist Ellen Fernandez-Sacco was raised by “flat-out racist” Puerto Rican parents who said they were white, though she suspected otherwise.

“I couldn’t bring Black friends home. I couldn’t have a Black boyfriend,” Fernandez-Sacco said. “But my dad used to sleep with pomade and the end of a nylon stocking on his hair. What were they hiding?”

Over a half-century later, Puerto Rican church records helped Fernandez-Sacco build a rare paper trail back to Africa. The 1810 burial record of her sixth-great-grandfather, Juan José Carrillo, described him as “free Black” and a “native of Guinea.”

“I was floored. I was so elated,” Fernandez-Sacco said.

Of the estimated 10.5 million enslaved Africans who landed in the Americas between 1501 and 1866, about 96% came to Latin America and the Caribbean. And while nearly half went to Brazil, Spanish Latin America received more than triple the number of enslaved Africans than what the mainland United States did.

And this history is reflected in the genes. A recent genetic study of over 6,000 Mexicans shows a near ubiquity of descent from enslaved people as well as slaveholders, with ancestries from West Africa observed in every Mexican state, “in agreement with historical records of shipping voyages from the transatlantic slave trade.”

Yet the notion that Latino and Black identities are separate or incompatible — and the reality of anti-Black racism — have deep historical roots. While African influence can be found in Latin American food, music and culture, the colonial caste system denigrated African heritage and favored light skin, making the term mejorando la raza (improving the race) a household phrase: It refers to a Latino whose partner or children are whiter than they are — in what’s considered a step up.

And in the U.S. and Latin America, the realities of racism pressured many families to identify as white despite Indigenous and Black roots. In the 2010 census, over half (53%) of Latinos identified as white only. In a Pew Research survey conducted in 2019 and 2020, roughly 12% of U.S. Latinos identified as Afro Latino.

A race to preserve history

Catholic Church records are among the few documents that recorded enslaved people’s names and families.

To help preserve these histories, Jane Landers, a historian at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, co-founded the Slave Societies Digital Archive in 2003. Today, SlaveSocieties.org offers free access to more than 3,900 digitized volumes of church and business records, totaling more than 750,000 images.

Landers calls her small-scale, fast-acting efforts “guerrilla preservation.” Local students and archivists in places like Brazil, Colombia, Cuba, Mexico and St. Augustine, Florida, receive donated digital cameras and learn to organize, preserve and digitize their own collections.

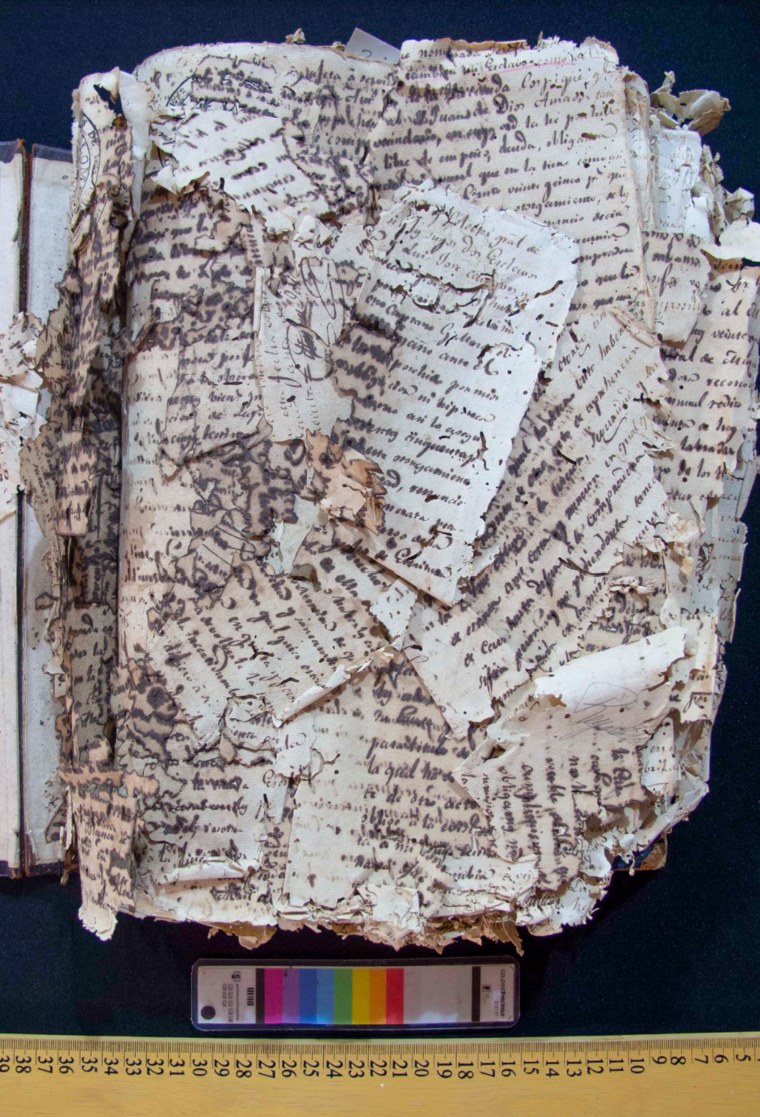

But what documents have survived are almost always faded, crumbling, torn, eaten by pests or otherwise damaged. Climate change, political instability, neglect and indifference also endanger archives.

Landers received a photo showing people in southern Cuba shoveling bundles of old records into a furnace, not caring for the history being lost.

“I just helped someone in Brazil get a grant for saving legal records in a little archive that wasn’t going to hold them any longer,” Landers said. “That happens a lot.”

As Landers’ team races against time to digitize, Vanderbilt professors are training AI to read and transcribe the entire Slave Societies collection. FamilySearch, another free online archive operated by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, increasingly uses computer indexing and full-text search on its more than 5 billion digitized images, including documents from every Spanish-speaking Latin American country and Brazil.

“You can find your families. They weren’t just property,” Landers said. “They were everything from soldiers to seamstresses to private business owners to slave traders, even.”

‘Follow these DNA trails’

Henry Louis Gates Jr., host of the Emmy-nominated PBS series “Finding Your Roots,” says it’s common for family lore to erase Black heritage. Singer-songwriter Carly Simon came on the show wanting to know more about her grandmother who claimed to be the king of Spain’s love child. Church records revealed that Simon’s grandmother was born in Cuba and descended from slaves, and DNA analysis showed that 10% of Simon’s ancestry was sub-Saharan African.

Simon’s grandmother “made up all these stories to hide her African roots,” Gates said. “It’s much easier to embrace fantasy than it is to think about rape, or cajoled sexuality at best.”

Gates says it’s also common for Latinos to have slaveholders in their family tree. Eight Latino guests on “Finding Your Roots” learned of slave-owning ancestors, including former NBA All-Star player Carmelo Anthony, TV host and lawyer Sunny Hostin and U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio. Looking at the baptismal record of his ancestor’s slave, Rubio commented to Gates, “If you baptize them, it’s because you believe they had a soul. … How then could you own them?”

Through SlaveSocieties.org, this reporter confronted his own family’s slave-owning past: Notary records from Cartagena, Colombia — once the largest slave port in South America — revealed an 1831 will of a previously unknown fourth-great-grandmother who left her daughter three enslaved youths as well as 100 pesos to purchase yet another slave. This reporter never thought that their humble Colombian immigrant grandmother, who sewed garments in New York sweatshops, could have been three and four generations removed from slave owners.

Exploring his own family tree, Texas-based genealogist Moises Garza uncovered both Afro Mexican ancestors and slave-owning forebears, reflecting the estimated 200,000 enslaved Africans brought to colonial Mexico. Garza first became interested in genealogy when he and his father were migrant workers in Texas, listening to his father’s family stories during long hours picking carrots. Over a quarter century later, Garza has compiled an online database with 1.1 million names from northeastern Mexico and Texas, and feels no need to distance himself from forebears who were conquistadors or slavers.

“I’m not going to say I’m embarrassed or going to apologize for what they did, because I have ancestors on both sides,” Garza said. “Some were the conqueror, some were the conquered. History is history and we learn from it. Or we get mad about it, but what’s the use of that?”

Gates said one is not restricted “to the good or bad things that your ancestors did — you want to go back to the original sin, look at the complicity between African merchants and elites and European merchants and elites over the course of the slave trade.”

“It’s a nasty and dishonest business to attempt to hold a person responsible for the stuff their ancestors did,” Gates said.

And yet uncovering the history of slavery is important, especially when so many Latin American families hid or intentionally forgot their African and Indigenous roots.

“Enslavement [and] genocide were designed to cut the ties that bind,” said Teresa Vega, an African American and Puerto Rican genealogist and public educator based in New York. “So you have to follow these DNA trails, figure out and flesh out your [family] trees and look for all possibilities.”

Vega’s parents separated when she was little, and it took a DNA test for Vega to connect with her paternal Puerto Rican family.

“I had been to Puerto Rico before, but I reconnected with my Taíno and Afro Indigenous side,” Vega said. “I feel like I’m 100% who I am.”

Giselle Rivera-Flores, a communications director in Worcester, Massachusetts, didn’t need a DNA test to know she was Afro Latina — her Puerto Rican family’s “Black skin and coarse hair” made that obvious. But finding out that 40% of her DNA matches Africans in countries like Cameroon, Congo, Nigeria, Senegal, Mali and Benin gave her “a sense of identity — one that no one can take away from me or debate about.”

While Rivera-Flores still has trouble convincing her mother and older relatives to embrace their Afro Latino heritage, she wants her three young children to know the insights she’s gained by knowing where she comes from.

“Staying true to who you are opens up a new perspective on how you view the world,” Rivera-Flores said. “It connects you with a lot of empathy for people.”

‘Here they are’

Following the loss of her Puerto Rican grandfather, filmmaker Alexis Garcia made her 2022 short film “Daughter of the Sea.” The film, which stars rapper Princess Nokia, draws inspiration from the Yoruba faith, an African religion practiced in Latin America.

Garcia first learned about the Yoruba faith at her grandmother’s botánica (religious goods store) in the Bronx, where her devout Catholic grandmother, Jerusalén Morales, called on Yoruba orishas (spirits) during spiritual readings and kept statues of orishas alongside Catholic saints. But it took years for Garcia to appreciate how the orishas directly connect her with her African roots.

“This is part of our inheritance. We didn’t have a material inheritance, but we have this spiritual inheritance,” Garcia said.

When Garcia tested her DNA, she found it “thrilling and emotional” to learn her direct maternal DNA — inherited from the grandmother who ran the botánica — comes from the Igbo people of Nigeria.

“To tell my mother and my grandmother the proof of who we are and where we came from … I feel like there was a spark from me to seven generations in the past,” Garcia said.

Garcia and her cousin Selina Morales have started a film production company, and they’re working on a feature film and a documentary on traditional healers in Puerto Rico. When they named the company, their grandmother once again provided inspiration: Botánica Pictures.

“Selina was told by our grandma that she was going to own a botánica. At that time she was like, ‘There’s no way I’m going to own a store selling candles,’” Garcia said. “When we landed on the name, we understood the prophecy from our grandmother.”

Garcia hopes to learn more about her family history. She has a photo of her great-great-grandmother, who was born enslaved in Puerto Rico around 1845, and she wants her work to motivate other Afro Latinos to connect with their Black identity and their past.

“The Black grandmother was always in the kitchen or at the back of the house, hidden away from the public. My aspiration is the liberation of ourselves and the liberation of our grandmothers,” Garcia said. “To no longer be like, ‘Where are they?’ Here I am. Here they are.”